ELI5 #3: What is the digital health formula? A la Sweetgreen

The building blocks necessary to build a digital health (services company), and some musings from the cheap seats about how to do it well.

hey :) I’m Anant and I’m another 20-something conjecturing about technology. My goal is to take complicated ideas, explain them simply, and develop a perspective. I’m writing to hold myself accountable to learning — hopefully you’ll find it interesting. Maybe you won’t. Thanks for reading either way.

helloo party people 🙌,

It’s been a while. Let’s keep it rolling. This time on digital health.

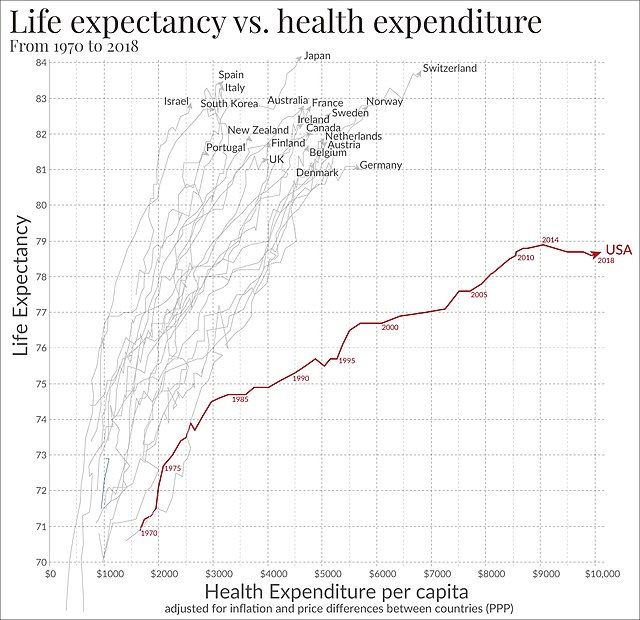

You’ve probably seen the below graph of life expectancy vs. health care expenditure like a dozen times (I saw it most recently on a blog post by a friend :)), and I’ve always found it jarring (let’s just say that the US’s high rates of homicides, suicide, and overdoses doesn’t really help).

One of our generation’s greatest issues will be contending with the spiraling cost of healthcare (in my last post, I talked about climate change). Part of our problem is that our country has an access issue. Here’s the proof: (1) six in ten Americans say they skipped or postponed getting care due to the cost; (2) 80% of US counties are healthcare deserts. And then, when people don’t get preventative care, they’re more likely to end up hospitalized with acute problems, which ends up being way *way* more expensive than if they’d gotten the care they needed in the first place.

The big opportunity with telehealth (why I’m excited about it, at least), is that it offers the possibility of flipping that on its head. Digital health is fundamentally about democratizing access to care — making it easier (cheaper, closer, faster) to see a provider. And what’s better? There are all kinds of consumer and market tailwinds here: young people care more about their health and aren’t willing to accept the friction-full waiting rooms typical of establishment providers. For an interesting “why now?” on telehealth, check out this post.

All this macro systems talk is sort of blah blah blah when you’re sick. A digital health founder friend of mine reminded me recently that, “people just want their problems solved; they don’t really care what happens behind the scenes.” It’s just like in any other category, but amplified with healthcare: when you’ve got a sprained ankle or a bout of acne or a stomach ache, you just want your problem to disappear.

So what’s the best way to do that for patients? Well, from where I’m sitting (the cheap seats, never having built a digital health company myself) there are some fundamental building blocks that need to be sorted out, the universe of which is knowable. Let me explain myself — you need: (1) a specialty / focus (e.g., mental health for professionals); (2) a way of acquiring patients (e.g., paid marketing on IG); (3) monetization strategy (e.g., billing insurance fee for service); and (4) provider strategy (e.g., 1099-therapists matched with patients through a marketplace). And there’s a finite number of combinations (or, my stats friends, is it permutations??) across these building blocks. Maybe you noticed that the e.g.’s basically describe telehealth mental health giants Headway and Grow Therapy.

This might sound flippant, but I mean it sooo earnestly: your menu of options feels a bit like building a Sweetgreen salad. Step 1: Pick a base (Kale, please!); Step 2: Pick a protein (Blackened tofu ftw); Step 3: Toppings (ugh yes, I know avocado is $2.50 extra); Step 4: Dressing (crazy if I mix two??).

It’s (obviously) much more complex for digital health startups, raising the question: what combination of building blocks (1) makes life easiest for consumers, (2) delivers highest quality outcomes, and (3) promises scalable economics. And an added layer of complication is that you likely need to do multiple things in each category well (e.g., bill fee for service and accept cash pay).

I’m not even close to having the “right” answers (and how best to build is definitely different depending on the problem you’re trying to solve), but let me walk you through some of the tradeoffs as I understand them.

Note: Under each building block, I’ve also included a section called “Notes from founders” — I wrote this piece and circulated it with a few digital health founders. They had some helpful nuance to add that I figured I’d share with you (edited for brevity).

Step 1: Choose your specialty / target demographic

The first thing you’ve got to figure out is: what problem are you going to solve and for whom? There are a lot of options here, from pediatric mental health (Handspring) to cardiometabolic care for older adults (Chamber Cardio). There are, of course, natural boundaries around the types of care that can be delivered virtually (lmk if you’ve got a good doctor for living room appendectomies), which whittles down your problem space.

I think the real question to ask here is not just what care *can* be delivered virtually, but rather what care is *better* delivered virtually. My evolving hypothesis is that virtual health is best in low-acuity, high-frequency care modalities, with limited need for “hands on the patient.” Expressable, for example, offers speech language pathology virtually, contending that care offered in the home and alongside primary caregivers translates to better outcomes for kids.

Notes from founders:

I think this mentality is why many digital health companies fail. You have to live, breathe, experience the problem to really understand it. Artificially selecting a specialty based on some variables has rarely worked (e.g. see all the conditions Ro strategically decided to target, tried and failed at). It’s worth emphasizing that this is where the metaphor may fail. Unlike with Sweetgreen, you shouldn’t choose the greens. The greens should choose you. Or put another way, everything depends on who the customer is. There’s probably only one salad mix that will work, and all the others will fail for a specific customer segment.

The viability of a specialty is not just what can be done *better* virtually, but also what are people willing to pay for. Better care doesn’t always get rewarded. There are specialties where virtual care would be very effective, perhaps more effective, but the willingness to pay is just not as high.

Step 2: Choose your distribution

Distribution is the hardest part of healthcare. You can be an amazing doctor, but you’ve got to figure out how to get your customers. (Side note: this part of business-building is becoming harder for basically every consumer business; maybe every business period). There are a few tried and true methods that I’ve seen:

Paid marketing — for example, Google ad words or paid influencer content on TikTok

Employer / insurance partnerships — a health benefit is offered through an employer or payor; sometimes a list of eligible parties is given to the telehealth company for them to “chase” down)

Patient referrals / health system partnerships — another care provider (e.g., a school counselor or a pediatrician for pediatric therapy) sends a patient to the company

Inbound / virality — people hear about your services from their friends and seek out treatment… you don’t have to lift a finger!

In healthcare, I’ve seen customer acquisition costs (the price companies pay in sales and marketing to attract a new customer) range from as low as $60 up to a couple thousand dollars. There’s no “right” answer here, but in order to make the economics work at scale, the cost of acquiring the customer has got to be less than the value earned from providing services to that customer. Basically, you want the cost to be as low as possible, ideally… zero (that’s obviously not a reasonable goal, but zero dollar CACs will make any VC’s mouth water). For that reason, referrals and inbound are seen as being the “holy grail” of distribution, and the greater share of patients you can get from these sources, the better. A particularly exciting telehealth company I was looking at recently (with strong virality) had >30% of patient volume coming from inbound, with plans to grow that over time.

Notes from founders:

Distribution is so important for healthcare companies because there is a lot of natural churn – e.g., you might only need a month of physical therapy. Like other services businesses, most digital health companies have to wake up every morning and re-fill their pipe with patients. If you’re able to retain customers for longer (e.g., people use talk therapy for years), your unit economics start to look better.

Step 3: Pick how you get paid

This is where our Canadian and UK friends start to shriek — now you’ve got to choose how you get paid. A couple different options here:

Cash pay — Patients pay out of pocket for the services they’ve received; In some cases, patients pay by service (that’s sort of the traditional model). Others, like Honeydew (dermatology) or Paloma Health (thyroid management), have subscription cash pay models where customers pay out of pocket monthly.

Fee for service — Patients receive the service and then you bill their insurance; this requires negotiating reimbursement contracts with the national payors (e.g., Cigna and Aetna) and the regional payors (e.g., Blue Cross Blue Shield of a particular state). This is sort of the go-to for digital health companies at all stages of growth (e.g., Grow Therapy, Marley Medical, Allara). One interesting tidbit: two different providers can offer the same service to the same patient billed to the same payor but get reimbursed different amounts. Negotiating these contracts is kind of the black box / underbelly of our healthcare system, but it ends up being make or break because reimbursement rates all flow down to the bottom line. I want to do a whole other post on how fees are negotiated.

An alternative arrangement might be to partner directly with health systems as a delegated provider, delivering services on their behalf that they bill for and receiving an agreed upon reimbursement in return

Value based care — Risk-bearing contracts in which a provider puts fees at risk and is paid not based on services rendered but rather outcomes achieved for a set patient population (e.g., you can think of this as a doctor getting paid a flat sum to keep a patient out of the hospital). There’s a ton of nuance here (e.g., per member per month models, capitation models, etc. — but we can save that for later). A founder I was talking to joked that he’d been in healthcare for decades and that value based care contracts have been “around the corner” nearly the whole time. There are some market segments, however, that are further along in this transition — primary care (e.g., Devoted Health) and nephrology (kidney care!), for example, have more risk bearing contracts

Traditionally, moving from cash pay to fee-for-service to value based care is seen as the “crawl - walk - run” of healthcare, meaning that everyone starts at the top of the list, and, by delivering positive outcomes for patients and sharing that data with providers, moves downward.

Interestingly, there’s some overlap between payment and distribution: maybe unsurprisingly, the less an individual needs to pay out of pocket for a service, the more likely they are to use it (remember, Americans don’t have much disposable income sitting around for healthcare). Put another way: greater insurance coverage means lower patient acquisition costs, sometimes dramatically so. I saw a company whose cost per patient acquisition went from >$1,500 / patient to $300 / patient as soon as they could bill insurance (see chart above).

Notes from founders:

More than 50% of Americans have a high deductible health plan now, and many cash-pay services are now cheaper than paying the insurance deductible. There are two forces working in the opposite direction. In many cases, taking insurance can lower the cost of care, and even if it doesn’t, there’s a psychological checkmark of, “They take my insurance” that helps conversions. On the other hand, with more people paying through HDHPs, they are more cost conscious and a growing number of people end up on cash-pay services even though they have insurance because those services are more affordable than insurance rates.

Dealing with payors sucks. National payors are really powerful and don’t want to pay you. You will need a whole team doing insurance operations, battling to get paid on claims and renegotiating contracts every year (e.g., this near disaster between United Health and Mount Sinai).

Most telehealth companies are simultaneously accepting cash pay, billing insurance fee for service where they have contracts, and trying (sometimes unsuccessfully) to transition relationships to value-based care

There's an inherent risk to building a healthcare service business that cannot be billed fee-for-service because 1) consumers expect to pay for healthcare with their insurance, and 2) insurance companies are generally only open to value-based care arrangements with providers that can demonstrate success and real economic savings, which most reliably is the case for providers that prevent an acute event, e.g. think about Equip preventing ER admissions

Step 4: Providers / business model

And then (probably obvious at this point) you’ve got to figure out what mix of providers and business model makes the most sense given all of the above. A couple things to consider:

Provider mix - Different providers are trained for different situations. To write a prescription, for example, you might need an MD or supervision from an MD (laws differ by state — gotta keep things interesting!). Providing the right kind of care requires thinking through what mix of providers enables high quality care on a cost basis that works at scale. Oula Health, for example, staffs using midwives and doulas (practitioners with long traditions of using highly effective, less invasive methods) alongside traditional doctors. Sol Health is using therapists in training to simultaneously address the therapist supply issue while providing low-cost therapy to Gen-Z clients.

Business model - Finally, you’ve got to figure out how to pay, train, and match your providers. In cases where there’s sufficient volume to fill a provider’s full schedule or you want to spend time on provider trading to standardize care, it might make sense to have full-time providers that sit on the company payroll (i.e., W2 employees eligible for benefits). In other cases, where providers want additional autonomy (e.g., to continue their existing practice on the side), it might make sense to have 1099 providers in a marketplace where providers taking on greater case load get paid more. There’s a bunch of different models in between too.

At the end of the day, telehealth companies are services businesses — paying providers is going to be the greatest cost in any healthcare business, so it’s important to figure out what provider mix and model delivers outcomes and scales.

Notes from founders:

Clinician employees are often highly skilled (and therefore very expensive). You also have to really add value for them to not leak off (e.g., you aren’t going to disintermediate DoorDash by going straight to your dasher, but your dietician…)

There is also real safety risk here. DoorDash isn’t managing customers’ health and they don’t need an escalation plan if someone tells their dasher they are going to commit suicide or are having a heart attack. Telehealth is hard because you often have to interface with people on the ground or have an on the ground presence to manage higher acuity cases.

Enablement layer & other components

Underlying all of this is the technology — workflows for patient intake and scheduling, eligibility verification and prior authorization, provider note-taking and coding, and billing. It’s framed as an afterthought here because I couldn’t hope to do it justice alongside all of the above, but so much cool, AI-enabled innovation at this layer: structuring traditionally messy healthcare data and training models on it (e.g., think of the use cases for a model that could predict the % likelihood of an intervention to work based on biomarkers unique to you); AI-enabled workflows to reduce healthcare admin (e.g., AI agents to execute routine eligibility verification workflows), empowering patients with their own data (e.g., to have a consolidated health history). And there’s so much more — hit me with more cool, good ideas that you’ve heard here :)

Notes from founders:

It is so much more complicated to build a telehealth business successfully under the hood. Great ideas fall apart due to inherent delays in things like government enrollments, credentialing timelines, etc.

If the thesis of the piece is that there is a well-defined way to start a digital health company, then my addendum would be there is a well-defined way to start a digital health company that struggles to make money :) It takes real ingenuity to make the puzzle pieces fit together.

Wrap-up

One final musing on the digital health services space is that these companies deviate from the typical underwriting strategy of venture-backed software in at least a couple of ways: (1) they tend to be lower margin because humans (almost all the time) have to be in the loop, and (2) these aren’t winner take all categories (Of course there are benefits to scale, like effective provider load balancing, but you can have multiple PT providers in a way you probably won’t have multiple marketplaces), making competition less stiff.

Private equity has entered the world of healthcare provision (with some real criticism about outcomes), so one cautionary note is that as VC does the same, we’ve got to be thoughtful about models and outcomes. The traditional “go fast and break things” tech mantra doesn’t work when you’re talking about people’s health.

I’ve been lucky to work alongside a number of super bright digital health founders in the last months — certainly seen a lot of companies in this category — and would love to talk to anybody that has insight in this space.

Love the Sweetgreen analogy - smart approach to break down the healthcare economy into mix and match services. Fun read!